GO語言實現區塊鏈Part2 Proof-of-Work

Introduction

In the previous article we built a very simple data structure, which is the essence of blockchain database. And we made it possible to add blocks to it with the chain-like relation between them: each block is linked to the previous one. Alas, our blockchain implementation has one significant flaw: adding blocks to the chain is easy and cheap. One of the keystones of blockchain and Bitcoin is that adding new blocks is a hard work. Today we’re going to fix this flaw.

Proof-of-Work

A key idea of blockchain is that one has to perform some hard work to put data in it. It is this hard work that makes blockchain secure and consistent. Also, a reward is paid for this hard work (this is how people get coins for mining).

This mechanism is very similar to the one from real life: one has to work hard to get a reward and to sustain their life. In blockchain, some participants (miners) of the network work to sustain the network, to add new blocks to it, and get a reward for their work. As a result of their work, a block is incorporated into the blockchain in a secure way, which maintains the stability of the whole blockchain database. It’s worth noting that, the one who finished the work has to prove this.

This whole “do hard work and prove” mechanism is called proof-of-work. It’s hard because it requires a lot of computational power: even high performance computers cannot do it quickly. Moreover, the difficulty of this work increases from time to time to keep new blocks rate at about 6 blocks per hour. In Bitcoin, the goal of such work is to find a hash for a block, that meets some requirements. And it’s this hash that serves as a proof. Thus, finding a proof is the actual work.

One last thing to note. Proof-of-Work algorithms must meet a requirement: doing the work is hard, but verifying the proof is easy. A proof is usually handed to someone else, so for them, it shouldn’t take much time to verify it.

Hashing

In this paragraph, we’ll discuss hashing. If you’re familiar with the concept, you can skip this part.

Hashing is a process of obtaining a hash for specified data. A hash is a unique representation of the data it was calculated on. A hash function is a function that takes data of arbitrary size and produces a fixed size hash. Here are some key features of hashing:

- Original data cannot be restored from a hash. Thus, hashing is not encryption.

- Certain data can have only one hash and the hash is unique.

- Changing even one byte in the input data will result in a completely different hash.

Hashing functions are widely used to check the consistency of data. Some software providers publish checksums in addition to a software package. After downloading a file you can feed it to a hashing function and compare produced hash with the one provided by the software developer.

In blockchain, hashing is used to guarantee the consistency of a block. The input data for a hashing algorithm contains the hash of the previous block, thus making it impossible (or, at least, quite difficult) to modify a block in the chain: one has to recalculate its hash and hashes of all the blocks after it.

Hashcash

Bitcoin uses Hashcash, a Proof-of-Work algorithm that was initially developed to prevent email spam. It can be split into the following steps:

- Take some publicly known data (in case of email, it’s receiver’s email address; in case of Bitcoin, it’s block headers).

- Add a counter to it. The counter starts at 0.

- Get a hash of the

data + countercombination. - Check that the hash meets certain requirements.

- If it does, you’re done.

- If it doesn’t, increase the counter and repeat the steps 3 and 4.

Thus, this is a brute force algorithm: you change the counter, calculate a new hash, check it, increment the counter, calculate a hash, etc. That’s why it’s computationally expensive.

Now let’s look closer at the requirements a hash has to meet. In the original Hashcash implementation, the requirement sounds like “first 20 bits of a hash must be zeros”. In Bitcoin, the requirement is adjusted from time to time, because, by design, a block must be generated every 10 minutes, despite computation power increasing with time and more and more miners joining the network.

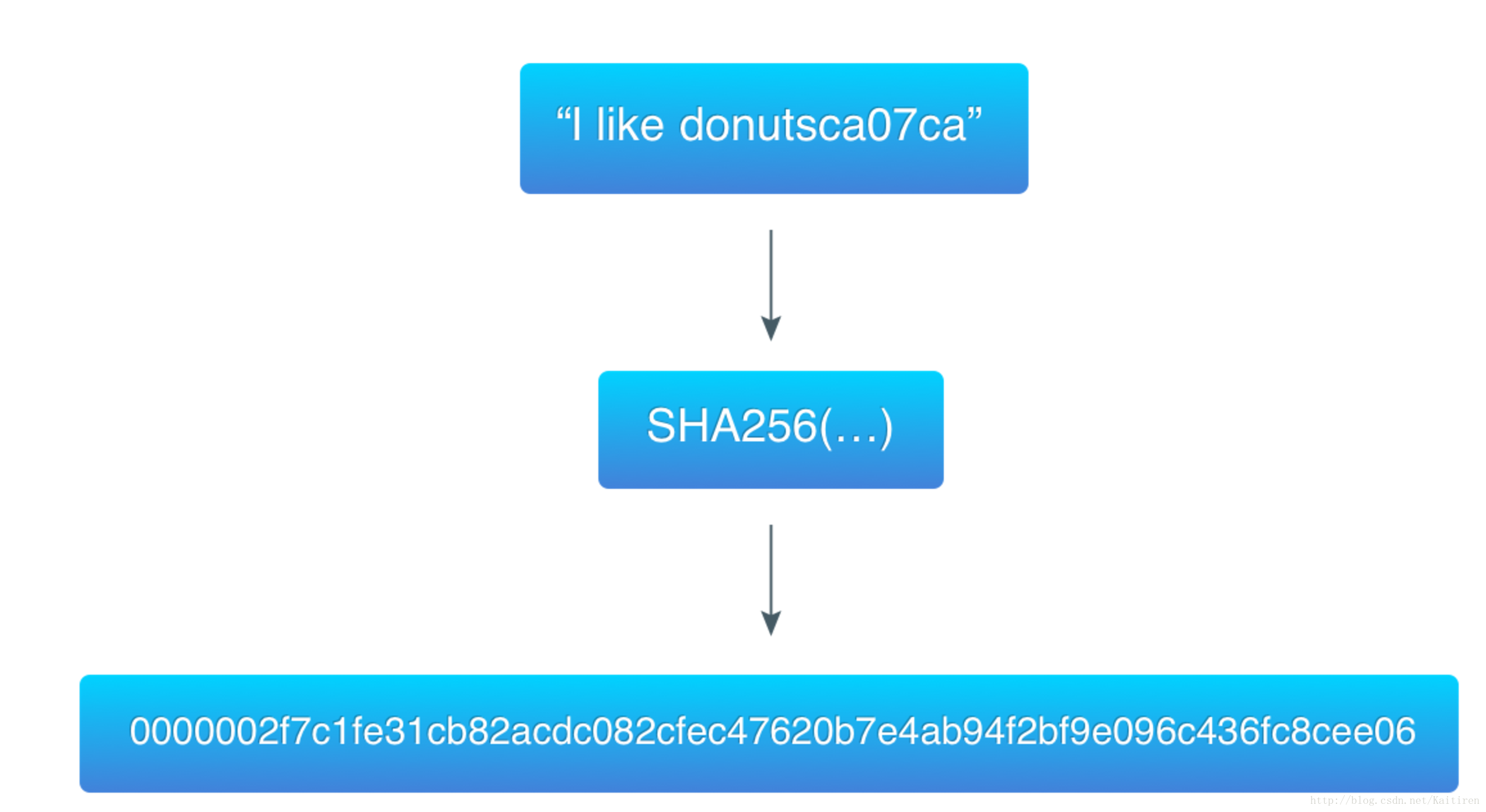

To demonstrate this algorithm, I took the data from the previous example (“I like donuts”) and found a hash that starts with 3 zero-bytes:

ca07ca is the hexadecimal value of the counter, which is 13240266 in the decimal system.

Implementation

Ok, we’re done with the theory, let’s write code! First, let’s define the difficulty of mining:

const targetBits = 24

In Bitcoin, “target bits” is the block header storing the difficulty at which the block was mined. We won’t implement a target adjusting algorithm, for now, so we can just define the difficulty as a global constant.

24 is an arbitrary number, our goal is to have a target that takes less than 256 bits in memory. And we want the difference to be significant enough, but not too big, because the bigger the difference the more difficult it’s to find a proper hash.

type ProofOfWork struct {

block *Block

target *big.Int

}

func NewProofOfWork(b *Block) *ProofOfWork {

target := big.NewInt(1)

target.Lsh(target, uint(256-targetBits))

pow := &ProofOfWork{b, target}

return pow

}

Here create ProofOfWork structure that holds a pointer to a block and a pointer to a target. “target” is another name for the requirement described in the previous paragraph. We use a big integer because of the way we’ll compare a hash to the target: we’ll convert a hash to a big integer and check if it’s less than the target.

In the NewProofOfWork function, we initialize a big.Int with the value of 1 and shift it left by 256 - targetBits bits. 256 is the length of a SHA-256 hash in bits, and it’s SHA-256 hashing algorithm that we’re going to use. The hexadecimal representation of target is:

0x10000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

And it occupies 29 bytes in memory. And here’s its visual comparison with the hashes from the previous examples:

0fac49161af82ed938add1d8725835cc123a1a87b1b196488360e58d4bfb51e3

0000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

0000008b0f41ec78bab747864db66bcb9fb89920ee75f43fdaaeb5544f7f76ca

The first hash (calculated on “I like donuts”) is bigger than the target, thus it’s not a valid proof of work. The second hash (calculated on “I like donutsca07ca”) is smaller than the target, thus it’s a valid proof.

You can think of a target as the upper boundary of a range: if a number (a hash) is lower than the boundary, it’s valid, and vice versa. Lowering the boundary will result in fewer valid numbers, and thus, more difficult work required to find a valid one.

Now, we need the data to hash. Let’s prepare it:

func (pow *ProofOfWork) prepareData(nonce int) []byte {

data := bytes.Join(

[][]byte{

pow.block.PrevBlockHash,

pow.block.Data,

IntToHex(pow.block.Timestamp),

IntToHex(int64(targetBits)),

IntToHex(int64(nonce)),

},

[]byte{},

)

return data

}

This piece is straightforward: we just merge block fields with the target and nonce. nonce here is the counter from the Hashcash description above, this is a cryptographic term.

Ok, all preparations are done, let’s implement the core of the PoW algorithm:

func (pow *ProofOfWork) Run() (int, []byte) {

var hashInt big.Int

var hash [32]byte

nonce := 0

fmt.Printf("Mining the block containing \"%s\"\n", pow.block.Data)

for nonce < maxNonce {

data := pow.prepareData(nonce)

hash = sha256.Sum256(data)

fmt.Printf("\r%x", hash)

hashInt.SetBytes(hash[:])

if hashInt.Cmp(pow.target) == -1 {

break

} else {

nonce++

}

}

fmt.Print("\n\n")

return nonce, hash[:]

}

First, we initialize variables: hashInt is the integer representation of hash; nonce is the counter. Next, we run an “infinite” loop: it’s limited by maxNonce, which equals to math.MaxInt64; this is done to avoid a possible overflow of nonce. Although the difficulty of our PoW implementation is too low for the counter to overflow, it’s still better to have this check, just in case.

In the loop we:

- Prepare data.

- Hash it with SHA-256.

- Convert the hash to a big integer.

- Compare the integer with the target.

As easy as it was explained earlier. Now we can remove the SetHash method of Blockand modify the NewBlock function:

func NewBlock(data string, prevBlockHash []byte) *Block {

block := &Block{time.Now().Unix(), []byte(data), prevBlockHash, []byte{}, 0}

pow := NewProofOfWork(block)

nonce, hash := pow.Run()

block.Hash = hash[:]

block.Nonce = nonce

return block

}

Here you can see that nonce is saved as a Block property. This is necessary because nonce is required to verify a proof. The Block structure now looks so:

type Block struct {

Timestamp int64

Data []byte

PrevBlockHash []byte

Hash []byte

Nonce int

}

Alright! Let’s run the program to see if everything works fine:

Mining the block containing "Genesis Block"

00000041662c5fc2883535dc19ba8a33ac993b535da9899e593ff98e1eda56a1

Mining the block containing "Send 1 BTC to Ivan"

00000077a856e697c69833d9effb6bdad54c730a98d674f73c0b30020cc82804

Mining the block containing "Send 2 more BTC to Ivan"

000000b33185e927c9a989cc7d5aaaed739c56dad9fd9361dea558b9bfaf5fbe

Prev. hash:

Data: Genesis Block

Hash: 00000041662c5fc2883535dc19ba8a33ac993b535da9899e593ff98e1eda56a1

Prev. hash: 00000041662c5fc2883535dc19ba8a33ac993b535da9899e593ff98e1eda56a1

Data: Send 1 BTC to Ivan

Hash: 00000077a856e697c69833d9effb6bdad54c730a98d674f73c0b30020cc82804

Prev. hash: 00000077a856e697c69833d9effb6bdad54c730a98d674f73c0b30020cc82804

Data: Send 2 more BTC to Ivan

Hash: 000000b33185e927c9a989cc7d5aaaed739c56dad9fd9361dea558b9bfaf5fbe

Yay! You can see that every hash now starts with three zero bytes, and it takes some time to get these hashes.

There’s one more thing left to do: let’s make it possible to validate proof of works.

func (pow *ProofOfWork) Validate() bool {

var hashInt big.Int

data := pow.prepareData(pow.block.Nonce)

hash := sha256.Sum256(data)

hashInt.SetBytes(hash[:])

isValid := hashInt.Cmp(pow.target) == -1

return isValid

}

And this is where we need the saved nonce.

Let’s check one more time that everything’s ok:

func main() {

...

for _, block := range bc.blocks {

...

pow := NewProofOfWork(block)

fmt.Printf("PoW: %s\n", strconv.FormatBool(pow.Validate()))

fmt.Println()

}

}

Output:

...

Prev. hash:

Data: Genesis Block

Hash: 00000093253acb814afb942e652a84a8f245069a67b5eaa709df8ac612075038

PoW: true

Prev. hash: 00000093253acb814afb942e652a84a8f245069a67b5eaa709df8ac612075038

Data: Send 1 BTC to Ivan

Hash: 0000003eeb3743ee42020e4a15262fd110a72823d804ce8e49643b5fd9d1062b

PoW: true

Prev. hash: 0000003eeb3743ee42020e4a15262fd110a72823d804ce8e49643b5fd9d1062b

Data: Send 2 more BTC to Ivan

Hash: 000000e42afddf57a3daa11b43b2e0923f23e894f96d1f24bfd9b8d2d494c57a

PoW: true

Conclusion

Our blockchain is a step closer to its actual architecture: adding blocks now requires hard work, thus mining is possible. But it still lacks some crucial features: the blockchain database is not persistent, there are no wallets, addresses, transactions, and there’s no consensus mechanism. All these things we’ll implement in future articles, and for now, happy mining!

相關文章

- GO語言實現區塊鏈Part7 NetworkGo區塊鏈

- GO語言實現區塊鏈Part6 Transactions 2Go區塊鏈

- GO語言實現區塊鏈Part4 Transactions 1Go區塊鏈

- GO語言實現區塊鏈Part3 Persistence and CLIGo區塊鏈

- GO語言實現區塊鏈Part1 Basic PrototypeGo區塊鏈

- GO語言實現區塊鏈Part5 AddressesGo區塊鏈

- 使用 Go 語言打造區塊鏈(二)Go區塊鏈

- 區塊鏈,中心去,何曾著眼看君王?用Go語言實現區塊鏈技術,透過Golang秒懂區塊鏈區塊鏈Golang

- 實戰區塊鏈技術培訓之Go語言區塊鏈Go

- go 語言與區塊鏈基礎講解Go區塊鏈

- 區塊鏈開發之Go語言—IO操作區塊鏈Go

- Go 語言區塊鏈測試實踐指南(一):GO單元測試Go區塊鏈

- 使用Go語言從零編寫PoS區塊鏈(譯)Go區塊鏈

- 區塊鏈背後的資訊保安(1)AES加密演算法原理及其GO語言實現區塊鏈加密演算法Go

- 比原鏈CTO James | Go語言成為區塊鏈主流開發語言的四點理由Go區塊鏈

- JavaScript實現區塊鏈JavaScript區塊鏈

- 區塊鏈背後的資訊保安(2) DES、3DES加密演算法原理及其GO語言實現區塊鏈3D加密演算法Go

- 區塊鏈背後的資訊保安(5) 對稱加密演算法的分組模式及其Go語言實現區塊鏈加密演算法模式Go

- 【區塊鏈技術實現】區塊鏈

- 【Go區塊鏈開發】手把手教你匯入Go語言第三方庫Go區塊鏈

- 雲+區塊鏈 實現區塊鏈技術的普惠應用區塊鏈

- Go語言實現RPCGoRPC

- go語言實現掃雷Go

- .Net Core實現區塊鏈初探區塊鏈

- 使用Javascript實現小型區塊鏈JavaScript區塊鏈

- 區塊鏈-NFT 的實現原理區塊鏈

- 在 iOS 中實現區塊鏈iOS區塊鏈

- [譯] 用不到 200 行的 GO 語言編寫您自己的區塊鏈Go區塊鏈

- 區塊鏈特輯——solidity語言基礎(三)區塊鏈Solid

- Red 語言建立基金會,發力區塊鏈區塊鏈

- 區塊鏈特輯——solidity語言基礎(六)區塊鏈Solid

- 區塊鏈特輯——solidity語言基礎(七)區塊鏈Solid

- go語言依賴注入實現Go依賴注入

- go語言實現ssh打隧道Go

- Go語言interface底層實現Go

- GO語言 實現埠掃描Go

- Go語言實現TCP通訊GoTCP

- 一文讀懂區塊鏈以及一個區塊鏈的實現區塊鏈